Submitted by L. Bixler on Mon, 13/11/2023 - 11:15

In a study published this week in National Science Review, led by Dr Yu Wu, a visiting researcher in the Zoology Department, and Dr Stephen Pates, a Herchel Smith Postdoctoral Fellow, the growth dynamics of a Cambrian predator were quantified for the first time.

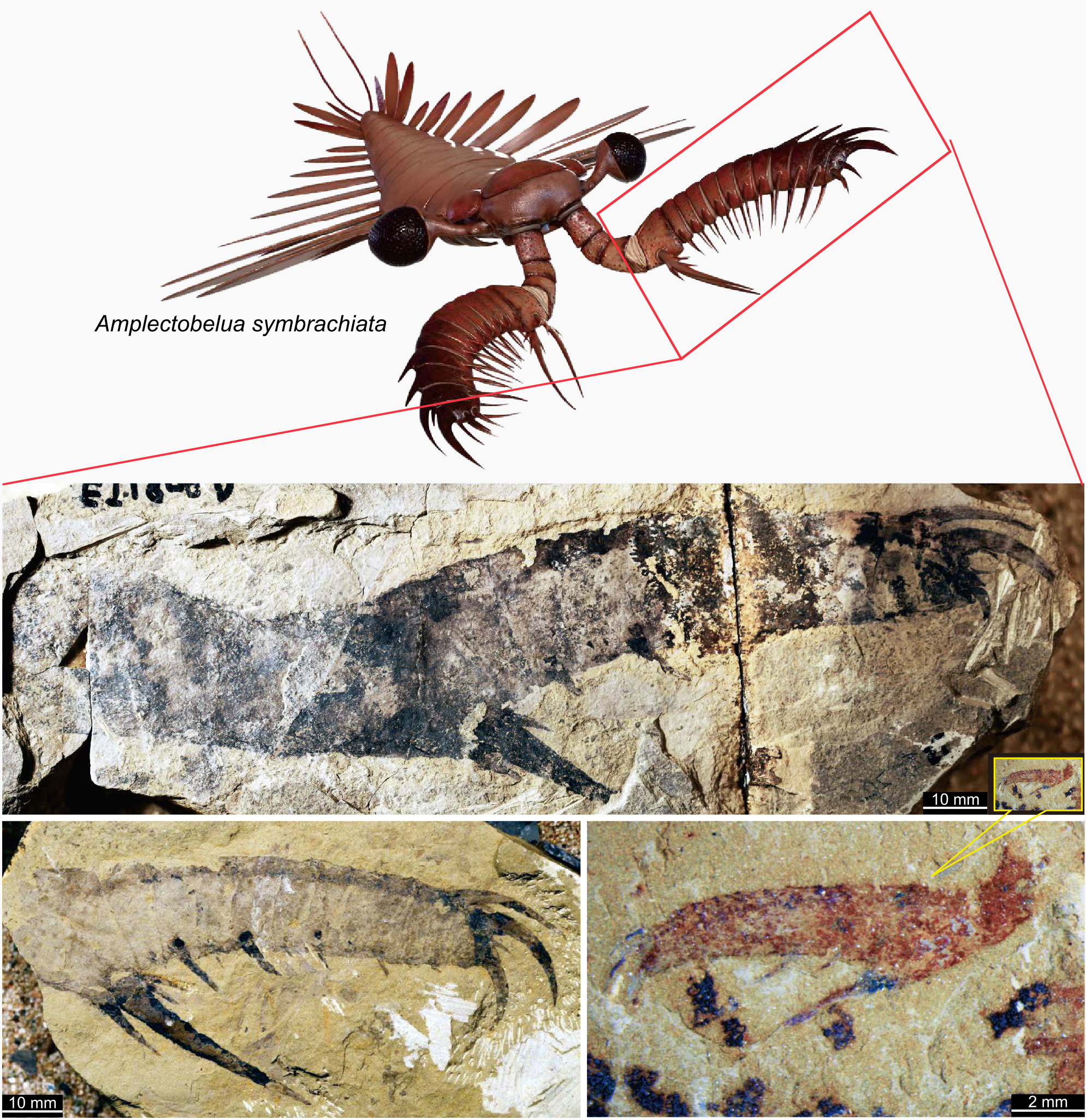

The rapid diversification of animals over 500 million years ago – often referred to as the Cambrian Explosion – saw the appearance of the first large swimming predators in our oceans. Amplectobelua symbrachiata, the large apex predator, are a member of the Radiodonta.

These are relatives of modern arthropods including modern lobsters, spiders and horseshoe crabs and were the largest reaching nearly one meter in length (Figure). These animals can be easily recognized in the fossil record by their fearsome spiny feeding appendages (Figure). Our understanding of how these animals grew and their changing ecological role through their life has been distinctly lacking.

In a study published this week in National Science Review, led by Dr Yu Wu, a visiting researcher in the Zoology Department, and Dr Stephen Pates, a Herchel Smith Postdoctoral Fellow, the growth dynamics of a Cambrian predator were quantified for the first time. As part of an international collaboration, hundreds of fossil specimens of the feeding appendages of Amplectobelua symbrachiata (ranging from less than 1 cm to more than 10 cm in length) collected from the famous fossil deposits of Chengjiang in China were carefully studied and statistically analysed.

The team determined both how the relative proportions of parts of the feeding appendages changed with size, and also quantified the growth rates in these animals for the first time. All analyses revealed that Amplectobelua symbrachiata appendages grew isometrically – juveniles and adult appendages had the same proportions (Figure). In addition, Amplectobelua symbrachiata grew more rapidly and likely over few growth stages than its modern arthropod relatives.

The unique position of A. symbrachiata as a large, active apex predator in ecosystems with large amounts of predation, without a fully arthropodized or sclerotized body may have facilitated this active lifestyle and rapid growing life history strategy.

Read the full article here: https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwad284