This obituary by Stuart Reynolds (1967, PhD 1970 – 1973) was first published in Antenna, the magazine of the Royal Entomological Society.

Sir Michael Berridge scaled the heights of global scientific eminence. He was without a doubt the most eminent insect physiologist of his time. His main discovery, lauded by many honours and prizes, was to discover the role of the intracellular second messenger inositol tris-phosphate (IP3) in mediating signalling between animal cells, and that this is accomplished through its action in mobilizing the release of divalent Calcium ions from intracellular stores. The significance of his work extended far beyond insects, having profound implications for the basic biochemistry, cellular regulation and intercellular signalling of all organisms, but readers of Antenna should not forget that Berridge was primarily a student of insect science and that for much of his career, insects were the main experimental organisms in his laboratory.

Berridge was born and grew up in Gatooma (now Kadoma), a small town in the then British colony of Southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe. He attended the University College of Rhodesia and Nyasaland (now University of Zimbabwe), where he was inspired by Professor Einer Bursell, an authority on the tsetse fly Glossina morsitans, vector of Trypanasoma brucei, the parasite that causes sleeping sickness.

Encouraged by Bursell and with a Commonwealth Scholarship to support him, Berridge left southern Africa for Cambridge, UK where he had secured a scholarship to study for a PhD in the department of Zoology under Sir Vincent Wigglesworth, then the most eminent insect physiologist in the world. His PhD project was to investigate nitrogen excretion in the cotton stainer, Dysdercus fasciatus (Hemiptera, Pyrrhocoridae) a topic which first introduced him to the physiology of fluid transport and insect Malpighian tubules.

Subsequently, Berridge went on to postdoctoral study in the United States, first with Dietrich Bodenstein at the University of Virginia (where he was a colleague of fellow postdocs and Wigglesworth alumni, Peter Lawrence and Brij Gupta) and then at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, where he worked with Bodil Schmidt-Nielsen, Howard Schneiderman and Michael Locke (and where he was a friend and colleague of Jim Oschman and Betty Wall). While in the USA Berridge worked on a number of different projects, all concerned in various ways with salt and water regulation in insects. Crucially, though, it was while at Case Western that together with Narayan G. Patel he discovered the stimulatory actions of serotonin and cyclic AMP on the salivary glands of the bluebottle Calliphora erythrocephala (Diptera, Calliphoridae). This was the experimental preparation that eventually propelled Berridge into the first ranks of twentieth century biological science.

In 1969 Berridge returned to Cambridge to join the AFRC Unit of Insect Physiology, located within the Department of Zoology, originally set up by Wigglesworth himself, but now directed by John Treherne. This was where he now began a serious fundamental investigation of the cell physiology of fluid transport using the blowfly salivary gland as a model. Probably not coincidentally, but planned by Treherne, the AFRC Unit also housed the laboratory (just across the corridor in fact) of Simon Maddrell, also working in the on the basic physiology of fluid transport but using the Malpighian tubules of the blood-sucking insect Rhodnius prolixus (Hemiptera, Reduviidae). Work in the two laboratories was complementary and often very closely linked. I was a student in Maddrell's lab at the time and can recall that expensive pharmacological reagents would often be shared.

Initially, Berridge's work focused on the mediation of serotonin action on salivary gland cells by the intracellular second messenger, 3'5'-cyclic AMP, but it soon became clear that serotonin's actions were in fact mediated by two separate receptors with different transduction mechanisms. In 1979, Berridge, together with a visiting researcher John N. Fain, discovered that the second arm of cellular regulation in blowfly salivary gland is mediated by hydrolysis of the membrane lipid phosphatidyl inositol to release IP3 as an intracellular second messager; IP3 in turn acts through an elevation of intracellular Ca. In 1983, he showed with Robin Irvine from Babraham that this same mechanism operated in a classical biochemical model of cellular activation, the pancreatic acinar cell. Their paper in Nature propelled Berridge into scientific stardom.

Berridge did not make this discovery out of nowhere; mobilisation of inositol phospholipids from cell membranes during cellular activation had been noted in the early 1950s by Mabel and Lowell Hokin at McGill University in Montreal, and Bob Michell at the University of Birmingham had speculated as early as 1975 that this might be of fundamental importance. But it was Berridge who picked up the hypothesis and ran with it. His outstanding success in doing this was partly serendipitous; the blowfly salivary gland is a superb experimental preparation - quickly prepared from readily available material, it responds rapidly to stimulation, works in vitro, and is (just) large enough to yield samples suitable for biochemical analysis. But also, after a decade's work on blowfly salivary glands, Berridge was mentally prepared to dissect apart the two cellular signalling pathways. Significantly, the Cambridge AFRC Unit allowed him to work as a full-time researcher with very few distractions. Perhaps most importantly, Berridge was not only a meticulous, focused and tireless researcher who did his experiments with his own hands, but was also widely read and prepared to recognise that insect salivary glands were excellent models for phenomena important right across the tree of life.

In 1990, the AFRC Unit moved from the Department of Zoology to a new home at the AFRC Babraham Institute. While he was there, Berridge's reputation grew and he travelled all over the world as a cell signalling celebrity. He was appointed honorary Professor of Cell Signalling at Cambridge and following his retirement as Head of Cell Signalling at Babraham in 2003, he was appointed an Emeritus Fellow at the Babraham Institute.

A man of extremely regular working habits, always gracious and good humoured, Berridge was universally admired. His scientific work was acknowledged by many prizes and distinctions. He was a Fellow of the Royal Society (1984) and received its Croonian Medal (1988) as well as the Royal Medal (1991). He was a member of EMBO (1991); a founding member of the Academy of Medical Sciences (1998); and a foreign associate of the US National Academy of Sciences (1999). Among others prizes, he received the Louis-Jeantet Prize for Medicine (1986), the King Faisal International Prize (1987) the Lasker Award in Basic Medical Sciences (1989), the Wolf Prize (1995/96); and the Shaw Prize in Life Science and Medicine (2005). He was knighted in 1997.

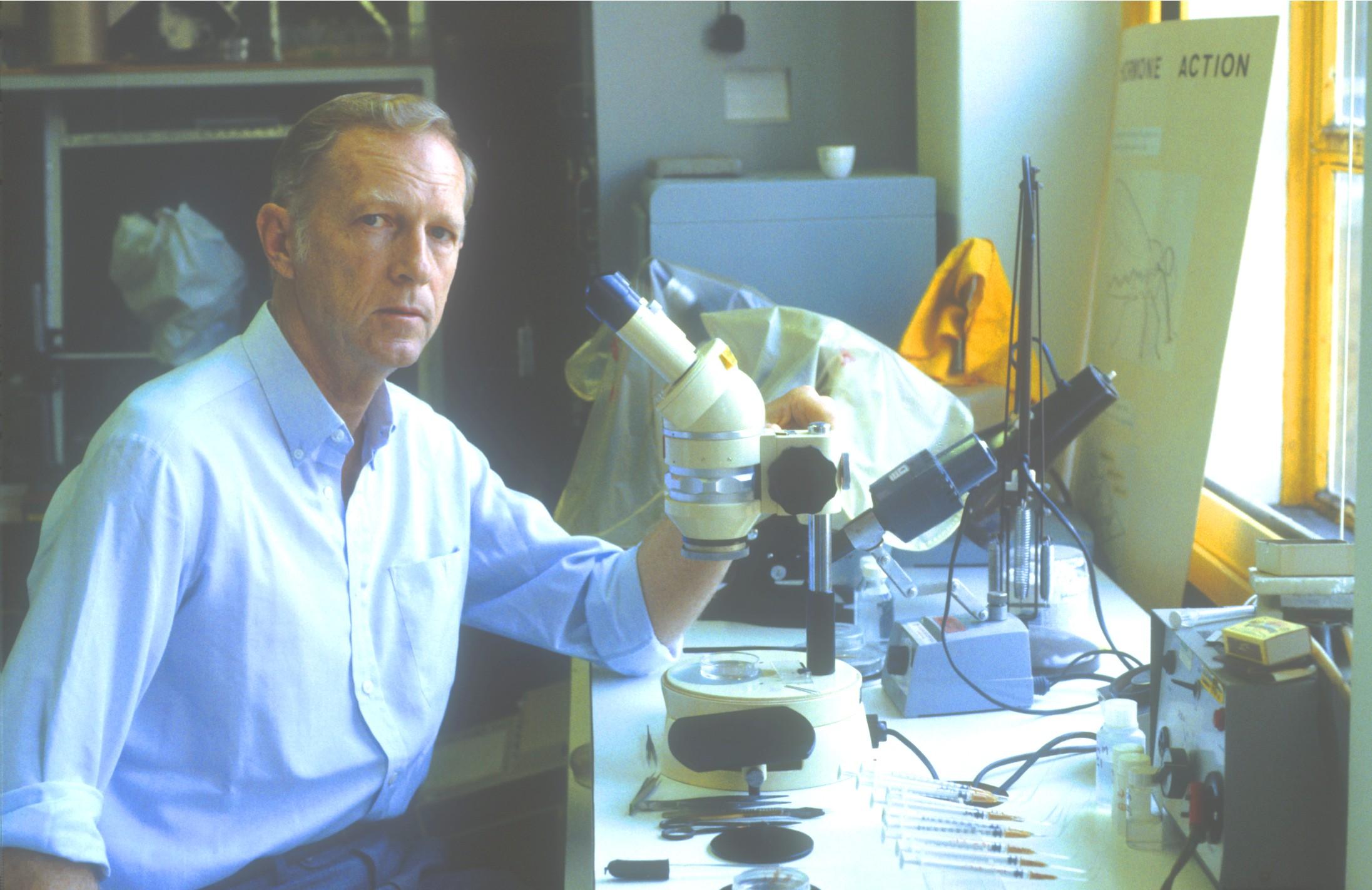

Picture: Mike Berridge in his laboratory (Babraham Institute)