Submitted by Administrator on Mon, 29/07/2013 - 15:36

Researchers in the Department of Zoology have a long history of studying the common cuckoo, the well-known brood parasite that lays its eggs in the nests of other species.

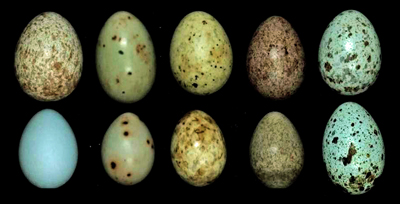

Female cuckoos belong to different genetic races called 'gentes,' a term coined by Alfred Newton, who became the University's first Professor of Zoology in 1866. Females belonging to different races selectively target specific hosts, and they lay an egg which often matches the colour and pattern of the host's egg remarkably well. Cuckoo mimicry has fascinated researchers since the time of Darwin and Newton, but most studies on the topic have relied on human assessments, which fail to account for bird vision.

Fast forward to 2011, when modern-day members of the Department of Zoology have developed methods to obtain a bird's-eye view of the cuckoo's egg-forging ability. Mary Caswell Stoddard and Martin Stevens applied models of bird colour vision to discover how well cuckoo eggs match host eggs from a host bird's point of view. Birds have much better colour vision than humans do. They have four colour cones in their retina, while humans only have three. The additional cone in birds is sensitive to ultraviolet wavelengths, which allows birds to see a whole range of colours humans are blind to.

To measure how well each cuckoo race matches its specific hosts, the researchers compared egg colours in avian colour space. In bird colour space, all colours can be represented based on how they stimulate the four bird colour cone-types. They revealed that some cuckoo distributions prominently overlapped those of their hosts, while others remained isolated in colour space.

"We found that cuckoos achieve better colour mimicry for hosts that are good at picking out the odd egg," explained Stoddard. "If the host is not a picky egg rejecter, the cuckoo will not have evolved a sophisticated degree of colour mimicry."

The cuckoo that parasitizes the dunnock is white with brown speckles, a poor match to the immaculate blue dunnock egg. Accordingly, the background colours of the dunnock-cuckoo and dunnock are completely isolated in avian colour space. Despite the obvious colour mismatch, dunnocks readily accept foreign eggs, and are thought to be at an early stage of the coevolutionary arms race, having not yet evolved host defenses.

But other cuckoo-host pairs appear to be further along in the arms race. The cuckoo that parasitizes the red-backed shrike, which is the strongest egg rejecter, achieves the highest colour overlap: the cuckoo and host distributions are completely superimposed in colour space. "The mimicry story is much more complex and exciting when we look through bird's eyes. The high degree of colour matching in some cases, and low degree in others, is not something that we could predict from our limited human perspective," said Stoddard.

Stoddard and Stevens published their findings this week in the journal Evolution.