March 2023 -

A Q&A with MPhil student, Jonny Timperley

This blog post was organised by Kate Howlett, a PhD student in the Insect Ecology Group.

Tell us about your MPhil research. What questions are you hoping to answer?

JT: My MPhil research is focused on assessing differences in the biodiversity, ecosystem functioning, and behaviour of arthropods between rainforest and oil palm systems in Liberia. In West Africa (oil palm’s native home), oil palm cultivation is expanding rapidly, but compared with Southeast Asia, relatively little has been researched on resulting ecological impacts. Liberia is a country that is incredibly ecologically important, being the third most-forested (by % of land area) country in Africa. However, the ecological impacts of oil palm cultivation in Liberia are little known. Therefore, we urgently need to quantify the ecological differences between the Liberian oil palm and rainforest systems. Arthropods are highly abundant in oil palm plantations, and their conservation is vital for maintaining biodiversity and, also, supporting palm oil yields, owing to the ecosystem services they provide. For instance, predatory insects and spiders are biological control agents of insect pests, and other arthropods (e.g., ants and beetles) contribute to decomposition and pollination. My research focuses on how arthropods differ in three different Liberian systems: industrial oil palm, country palm (small-scale farms owned, and managed, by locals), and natural rainforest. More specifically, the questions I aim to answer are: (1) Do rainforests support more abundant and compositionally different arthropod communities than oil palm systems? (2) How do levels of ecosystem functioning in oil palm plantations differ from those in rainforest? And (3) Do ants in oil palm plantations exhibit different behaviour patterns to those in rainforest? My research will provide important baseline ecological data in this understudied region, allowing a comparison for future work. I also hope to inform the development of management strategies to conserve arthropods while enhancing oil palm production, such as increasing the biodiversity of arthropod predators instead of applying harmful, chemically intensive pesticides within oil palm landscapes.

What led you here?

JT: I began studying oil palm during the third year of my undergraduate degree at the University of Nottingham. Due to COVID-19, I had few opportunities to conduct my own fieldwork for my third-year research project. Luckily for me, Dr Sarah Luke (formerly a Research Associate in the Insect Ecology Group) was my designated supervisor for the project and very kindly offered to provide me with data that she had collected in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo. The project focused on the design of riparian buffer strips (strips of preserved natural habitat alongside rivers/waterways) and, more specifically, how the width and habitat quality of these buffers impact tropical freshwater insects. With the aim of continuing my studies on insects and/or oil palm, I was very excited to discover that my current supervisor, Dr Michael Pashkevich, was offering a master’s project to assess socio-ecological differences between Liberian land-use systems. Having focused my research proposal on insects, I am now very happy to continue my research on both insects and oil palm, whilst gaining important and exciting fieldwork experience in Liberia!

What first sparked your interest in tropical ecology/conservation?

JT: I have always been extremely interested in animals, having grown up near to Salisbury Plain (the biggest remaining area of chalky grassland in northwest Europe). My parents are also passionate about wildlife, and therefore I owe a lot of my interest in ecology and conservation to them. Throughout my childhood, they consistently fed me facts and interesting information about certain animals/plants and watched countless wildlife documentaries with me. Whilst watching these documentaries, I was always very curious and excited by tropical wildlife, as well as rainforest ecosystems. Being passionate about both these, it comes hand-in-hand with being concerned about the rates of deforestation and biodiversity declines in these regions. Therefore, I aim to have a career in conservation to help in any way possible to protect, or best manage, these precious and naturally beautiful regions.

What is your favourite part of your work?

JT: For me, the most exciting part of my work is the opportunities it brings, such as working with the Insect Ecology Group, going to Liberia for eight weeks to conduct fieldwork, teaching a biodiversity workshop at the University of Liberia, and presenting at the British Ecological Society Annual Meeting in December 2022. I have just finished my fieldwork, and I thoroughly enjoyed working, and making very good friends, with the local partners of the project. They gave me interesting insights into the history and culture of Liberia, as well as making me constantly laugh throughout the trip. All of these are giving me great experience and are making me love my education, something that I would definitely not have said five years ago!

What are you looking forward to the most?

JT: In the short-term, I am very much looking forward to seeing the results of my thesis and completing the biggest project that I have done to date. In the long-term, I have been applying for PhDs, and therefore I hope to continue tropical research in the coming years.

What are your next steps?

JT: I have just completed my fieldwork in Liberia, and therefore my next steps are to identify the thousands of collected arthropods to order-level, begin analysing my other collected data, and start writing up my thesis.

February 2023 -

A Q&A with new PhD student, Sacchi Shin-Clayton

This blog post was organised by Kate Howlett, a PhD student in the Insect Ecology Group.

Tell us about your PhD research. What questions are you hoping to answer?

SSC: My PhD is looking at restoring landscapes in, and surrounding, agricultural crops, specifically looking at Riparian Ecosystem (river margins) Restoration in Tropical Agriculture (RERTA). Often, when we hear ‘conservation’, we think of preserving our remaining natural forests. While there is no denying the importance of this, equally crucial is restoring degraded landscapes which we have modified through human activities. Agriculture is one of the leading causes of landscape modification worldwide and is continuing to intensify due to the growing demands on food security. Therefore, a critical step for our future is finding a way to simultaneously maximise both agricultural output and ecological conservation within the same space. My PhD project focuses on how to restore and maintain healthy river margins within oil palm plantations in Indonesia. Since 2018, four treatments have been trialled at two river sites, in the hopes that we can determine which protocol results in the highest return for both forestry and biodiversity. What I hope to answer is not only which planting method is best for restoration, but also which method provides benefits for agricultural output. For example, would increasing the vegetation in the river margin naturally promote a reduction in the need for pesticides with the return of animals, that prey on crop pest species, to these landscapes? Further, would the resulting reduction in pest species and reliance on pesticides thereby increase the profit margins for the oil palm companies due to a lower cost-to-yield ratio? These are just a couple of the questions I hope to answer through the project, and I am very hopeful for future policies and landscape matrices to reflect this integration between agriculture and nature.

What led you here?

SSC: I was always interested in the nature surrounding me. I was fortunate to be able to live in various countries growing up, including Japan and New Zealand, and noticed changes in the landscape and how each culture treats nature. When I began my tertiary studies in New Zealand, I pursued this interest by studying ecology. New Zealand has two major economic incomes, nature tourism and agriculture. This clash intrigued me as, often, dairy farming results in extensive landscape clearing and pollution from run-off which conflicts with preserving nature for tourism. I decided to explore this by studying conservation ecology in my postgraduate studies, in the hopes of understanding possible solutions. Once I graduated, I worked in forest conservation. Although this was extremely fulfilling, I noticed there is a distinct disconnect between conservation and development, often being treated as completely diametrically opposed concepts. This is what motivated me to look into alternative methods that could resolve this conflict, such as farming using insects for pest control rather than pesticides, and that is how I came across the RERTA project description.

What first sparked your interest in tropical ecology/conservation?

SSC: In the tropics, land modification for agriculture is some of the highest rates worldwide. This drew my attention as a conservation ecologist as these landscapes are also some of the world's leading biodiversity hotspots. Therefore, effective conservation policies that reflect the interests of multiple stakeholders, such as agriculture and conservation, is not only needed but critical for the stability of the entire globe’s future.

What is your favourite part of your work?

SSC: My favourite part of being within research is the opportunity to collaborate with leading experts around the globe in restoration ecology. This project was built from an agreed collaboration between multiple partners, academic and industry, which is becoming increasingly important when trying to create effective policies that are more likely to be adopted by all partners, and for continued participation.

What are you looking forward to the most?

SSC: For the past five years, the data from the on-going experiments has continued to be collected despite numerous challenges that have occurred, such as COVID-19. Now, it is time to process and analyse what treatments have yielded the best results. This includes analyses on vegetation, ecosystem function, biodiversity, and agricultural output. This is a very exciting time to join the project and be able to track how the efforts by the team, and all our collaborators, have produced in terms of the project.

What are your next steps?

SSC: Not only are we looking at which treatment has resulted in the highest return in nature and agriculture so far, but which treatment will continue to operate in this synergistic system in the future climate. This is critical not only for future food security, but also for ensuring the climate does not continue to destabilize. Therefore, my next steps for the RERTA project are introducing new experiments to these river margins to capture which protocol has led to the highest resilience to the impending climate shifts we expect in the tropics.

January 2023 -

New paper: Wildlife documentaries present a diverse, but biased, portrayal of the natural world

This blog post was written by Kate Howlett, a PhD student in the Insect Ecology Group and lead author of the paper. Please hover the images for captions.

In wealthy countries, indirect, technology-mediated experiences of nature, such as through television programmes or social media are increasingly replacing direct experiences of nature, such as time spent in parks or forests. Portrayals of nature on television and social media are often edited for entertainment purposes and may prioritise aesthetics or excitement over scientific accuracy or realism. Alongside this, biases exist within public awareness and conservation research towards larger, charismatic groups of organisms, such as mammals. Smaller, more unfamiliar groups, such as invertebrates, are often overlooked, attracting less funding and public interest. This could potentially increase their risk of extinction, despite vital contributions to ecosystem functioning. In this context, it is important to understand how different types of media contribute to public awareness of biodiversity and its threats, since these portrayals have the potential to exacerbate or amend existing biases in awareness.

We sampled an online film database to understand whether there are biases in portrayals of the natural world in wildlife documentaries and whether conservation messaging within these kinds of films has changed over time. We randomly sampled 105 documentaries, evenly spread across the last seven decades, recording all organisms, habitats and mentions of anthropogenic threats to biodiversity, and whether or not conservation was mentioned. Afterwards, we identified each organism to the most precise level possible from the way in which it was referred to in the documentary.

The documentaries featured a wide range of animals and habitats. However, when compared to the actual numbers of described species in each group, the films consistently overrepresented mammals and birds, and consistently underrepresented invertebrates and plants. There was high variability in the representation of reptiles, fish and insects across time. The documentaries represented a range of habitats, the most common being tropical forest and the least common being deep ocean. While 41.8% of mentions of vertebrates were identifiable to species, just 7.5% of invertebrate mentions and 10% of plant mentions were identifiable to species. Overall, 16.2% of documentaries mentioned conservation, but almost 50% of documentaries in the current decade mentioned conservation. 22.1% of documentaries mentioned anthropogenic impacts but none before the 1970s, while the relative focus given to different anthropogenic threats did not always mirror their relative severity in the real world.

Our results show that documentaries provide a diverse picture of nature with an increasing focus on conservation, potentially raising awareness of conservation among audiences. However, documentaries also overrepresent vertebrates compared to invertebrates and plants, potentially directing more public attention towards these taxa. We suggest widening the range of taxa featured to redress this and call for a greater focus on threats to biodiversity to improve public awareness of the causes of biodiversity loss.

You can read the published paper for free by clicking here.

July 2022 -

A Q&A with new research assistant, Matthew Hendren

This blog post was organised by Kate Howlett, a PhD student in the Insect Ecology Group. Please hover over the images for captions.

What is your new role in the Group?

MH: I am a research assistant, currently working on quantifying canopy structure of 54 sites in and around six different oil palm plantations in Southeast Liberia, and creating R-scripts to analyse these data. Further down the line, I will be photographing and classifying spider specimens from these sites, using them as an overall indicator of ecosystem health, and helping to compile a species identification guidebook that will become freely available online.

What led you here?

MH: I have always been interested in the vast diversity of life and the incredible array of strategies each species utilises to overcome hurdles at developmental, ecological and evolutionary scales. Seeing such richness first-hand on a research expedition to the Chiquibul rainforest was particularly enlightening and working alongside some very inspiring people confirmed my love of the field. We were especially lucky to have the knowledge and experience of the local rangers, and Dr Jake Snaddon, who spent his childhood there, and to whom I am particularly grateful for his encouragement.

What first sparked your interest in tropical ecology/conservation?

MH: Given the historical models of human development to the detriment of natural systems, I share the opinion that we must close the gap of mutually exclusive prosperity and, while biodiversity is, of course, so much more than its value to us, the innumerable years of cumulative evolutionary innovation are a potential treasure trove of solutions to a more harmonious coexistence with nature. I firmly believe in conservation and viewing nature as a technology we can learn from, as the extinction of a species is not only a tragedy in the end of its lineage, but also the death of potential in fields such as medicine or biomimetics, and arguably diminishes the ability to understand our own place in the world.

What is your favourite part of the job?

MH: The feeling that I am spending my time on something meaningful, working on a fascinating project with a friendly team, each of whom have produced and are currently working on marvellous projects, right next-door to a zoological museum in a building named after the man whom I—along with countless others, I’m sure—idolise, what’s not to love? In addition, the flexibility this position affords is great, allowing my tasks to be tailored to really make the most in terms of skill development.

What are you looking forward to?

MH: Collaborating with incredible people, seeing museum collections usually kept behind closed doors, and learning as much as I can during my stay.

What are you hoping to do next?

MH: I would love to gain more field experience, and complete a Masters of Research in the biological sciences to deepen my understanding of all aspects of zoology, and develop my photographic portfolio.

June 2022 -

Rewilding reptiles: Using lizards to restore landscapes in South Australia

This blog post was written by Tom Jameson, a PhD student co-supervised by Ed Turner and Jason Head, member of the Vertebrate Palaeontology Group and honorary member of the Insect Ecology Group. Please hover over the images for captions.

Guuranda (the Yorke Peninsula in South Australia) is a landscape of gently rolling hills, vast fields of grain stubble and dusty sheep. As you approach the coast, remnant patches of native shrub give way to sand dunes and mangroves, white sand beaches and an azure sea. At the very tip of the Peninsula lies Dhilba Guuranda-Innes National Park, a remaining swathe of native mallee bushland made up of stringy bark gum-trees and silent salt lakes.

This is a beautiful but damaged landscape. Introduced foxes and cats have decimated populations of native animals, leading to the local extinction of most marsupial species. On top of this, large-scale land clearances have left only fragments of native habitat scattered across the landscape.

There is a solution—the Marna (healthy/ prosperous) Banggara (country) Project. This Project aims to restore the landscape of the Yorke Peninsula through rewilding—reintroducing locally-extinct native species to restore lost ecological processes. This approach benefits both the native landscape and agricultural productivity, as well as providing new economic opportunities for ecotourism in the area.

The Marna Banggara Project is a partnership between traditional owners (the Narungga, in whose language the project is named), farmers, NGOs and government, with research being carried out to support the project by local and international universities. Since on-ground work started in 2019, the project has made great progress. This includes erecting a 25 km anti-predator fence to enclose the 150,000 ha project area, intensifying control of fox and cat populations leading to the recovery of native animals and a decline in lamb mortality, and reintroducing the critically endangered brush-tailed bettong (Bettongia penicillata) to the region in 2021.

So where does a Cambridge PhD student come into this? As part of my PhD, I’m researching the role that reptiles play in rewilding projects, so I’ve joined the Marna Banggara Project to investigate how reptiles can contribute to the Project’s goals.

Within the Yorke Peninsula ecosystem, the largest native predator and scavenger is a reptile, the heath goanna (Varanus rosenbergi), a species of monitor lizard growing up to 1.5 m long. Top predators provide important services to ecosystems by controlling populations of native species, as well as reducing populations of invasive agricultural pests that can damage both native vegetation and crops. Scavengers also play an important ecological role in removing carcasses, supporting nutrient cycling and reducing the transmission of disease to native species, livestock and humans. As such, the heath goanna is an important part of the Yorke Peninsula ecosystem.

However, to date very little is known about the heath goanna population on the Yorke Peninsula. I’m therefore conducting research to gather baseline population data on the Yorke Peninsula heath goannas, figuring out exactly where they are found and how many individuals remain. I’m also quantifying the services they provide to the ecosystem, carrying out field experiments to assess their roles as predators and scavengers. The goal of all this work is to use the data I gather to build a management and rewilding plan for heath goannas as part of the Marna Banggara Project.

Working with the Project remotely from Cambridge, I used long-term monitoring data to build a picture of goanna populations on the Peninsula. Invasive and native scavengers have been closely monitored across the area since 2014, using hundreds of baited motion-sensitive cameras. From these data, I’ve been able to map the current range of the Yorke Peninsula goanna population.

From February to May, I was lucky enough to be living out on the Yorke Peninsula, carrying out further research. I was living right in the middle of Dhilba Guuranda-Innes National Park in a cottage in the ghost town of Inneston, alongside kangaroos and emus. Inneston was a gypsum mining town abandoned in the 1930s. Over time, the town has slowly been swallowed up by the bush, with just a few houses preserved for use by researchers and tourists.

From this base, I’m conducting experiments to quantify the role of reptiles as scavengers. I’m using a series of feeding stations, baited with rat carcasses, that exclude different kinds of animals. By monitoring what species arrive with motion-sensing cameras and recording removal of carcasses, I can quantify how important different groups of animals are as scavengers.

Preliminary results suggest that scavenging vertebrates are important for reducing incidence of disease from carcasses, with visits by vertebrate scavengers to feeding stations reducing the number of harmful blowflies breeding in a carcass. Invasive predators like foxes are doing quite a lot of scavenging, so it’s important that replacements (like goannas) are in place as foxes are removed from the landscape.

My findings indicate that heath goannas are going to play an important role in the rewilding of the Yorke Peninsula. When it comes to rewilding, reptiles have often been overlooked and ignored in favour of mammals. As rewilding projects become more common in parts of the world with populations of large reptiles (like Australia), it is important that conservation plans account for the role that reptiles play.

More than anything else, the Marna Banggara Project is a project of hope. Against a global backdrop of catastrophic climate change, continued habitat loss and mass extinctions, rewilding projects like Marna Banggara offer an alternative. Not content to just protect the fragments of remaining habitat, rewilding projects push back, restoring ecosystems and healing environmental wounds. It’s been an absolute privilege to work on the Marna Banggara Project alongside inspiring scientists, land managers and traditional owners. I’m looking forward to seeing the Project progress and the Yorke Peninsula becoming a little more wild, one lizard at a time.

Twitter: @TomJameson_Zoo

Instagram: @tjinthewild

The Marna Banggara Project is jointly funded through the Northern and Yorke Landscape Board, the Australian Government’s National Landcare Program, the South Australian Department for Environment and Water, WWF-Australia and Foundation for National Parks & Wildlife. Other partners actively involved in developing and delivering the project include Regional Development Australia, South Australian Tourism Commission, Zoos SA, FAUNA Research Alliance, BirdLife Australia, Nature Conservation Society of SA, Narungga Nation Aboriginal Corporation, Primary Producers SA, Primary Industries and Regions SA, Conservation Volunteers Australia, Legatus Group, Yorke Peninsula Council, Yorke Peninsula Tourism and the Scientific Expedition Group.

May 2022 -

New paper: Riparian buffers made of mature oil palms have inconsistent impacts on oil palm ecosystems

This blog post was written by Michael Pashkevich, a research fellow in the Insect Ecology Group and lead author of the paper. Please hover the images for captions.

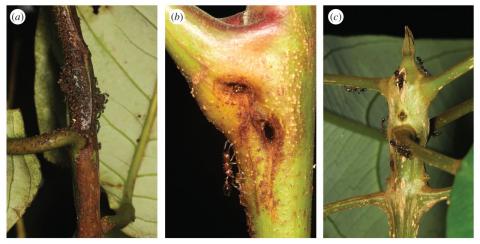

About half of the Insect Ecology Group works in oil palm agriculture. This crop is grown to produce palm oil, which is the most traded vegetable oil worldwide and is found in products ranging from lipstick to instant noodles. Conversion of natural habitat to oil palm plantations leads to substantial declines in biodiversity and changes in ecosystem functioning. However, once oil palm plantations are established, management strategies can be used to improve levels of biodiversity and ecosystem functioning within oil palm plantations, possibly resulting in benefits to crop yields. For instance, if management increases the number of beneficial insect pollinators, we might expect higher-yielding oil palm plantations.

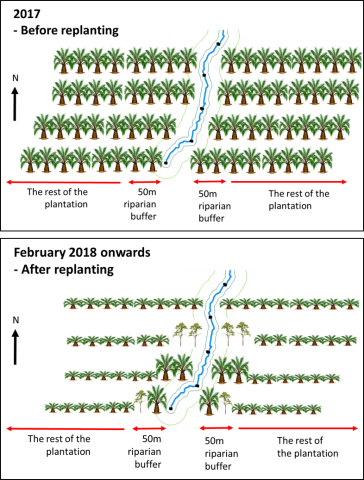

There are several ways to improve levels of biodiversity and ecosystem functioning in existing oil palm plantations, but a particularly promising approach is to retain riparian buffers (areas of land made of mature oil palms, surrounding waterways in croplands) when oil palms are replanted. These “mature palm buffers” are more structurally complex than surrounding cultivated areas, and receive lower input of pesticides, herbicides, and fertilisers. Owing to their management, we might expect mature palm buffers to have different levels of biodiversity and functioning than the surrounding cultivated oil palm landscape. However, whether this is the case has yet to be explored.

In a new study, published earlier this year in Ecological Applications, we set out to assess the benefits of mature palm buffers in replanted oil palm ecosystems. To do this, we sampled a chronosequence of oil palms in Sumatra, Indonesia. A chronosequence is a set of sites that have similar characteristics (i.e., in this case, all sites were oil palm plantations) but differ in age. All sites in our chronosequence had mature palm buffers, allowing us to assess the effects of mature palm buffers on the ecosystem of oil palm plantations of various ages. Specifically, we measured environmental conditions and levels of arthropod biodiversity. We took our measurements in three locations: within mature palm buffers, just outside buffers in the cultivated oil palm landscape, and very far away from buffers in the cultivated oil palm landscape.

We found that mature palm buffers can have environmental conditions (canopy openness, variation in openness, vegetation height, ground cover, and soil temperature) and levels of arthropod biodiversity (total arthropod abundance and spider abundance in the understory microhabitat, and spider species-level composition in all microhabitats) that are different from those in the surrounding cultivated oil palm landscape. However, these differences were not consistent across our studied chronosequence, indicating that any benefits of mature palm buffers to biodiversity are not consistent across the oil palm commercial life cycle.

Our findings suggest that, if the goal of maintaining riparian buffers within oil palm systems is to consistently increase habitat heterogeneity and improve biodiversity across the oil palm commercial life cycle, then different management of mature palm buffers or adjustments to their design are needed. One option could be to plant native forest trees amongst, or in place of, the mature oil palms. Studies in Jambi, Indonesia show that planting native rainforest trees can improve structural complexity and biodiversity in oil palm systems.

In our Riparian Ecosystem Restoration in Tropical Agriculture (RERTA) Project, we are exploring four different ways of designing riparian buffers, and assessing the relative benefits of each design to biodiversity, ecosystem processes, and yields in replanted oil palm plantations. As additional studies occur, it will be possible to identify strategies to maximise the benefits of riparian buffers on oil palm ecosystems. Once implemented, these strategies can contribute towards more sustainable development of the global palm oil industry.

You can read the published paper for free by clicking here.

April 2022 -

Conserving butterflies, past and present

This blog post was written by Matt Hayes, a PhD student in the Insect Ecology Group. Please hover over the images for captions.

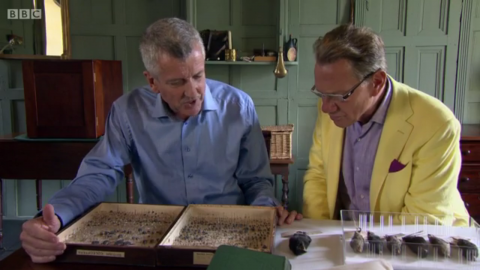

It has been an exciting few months for me as I started my PhD in January but have also been helping the team at the University Museum of Zoology in Cambridge (UMZC) with the new Butterflies Through Time exhibition, which opened on the 15th March.

The exhibition comes at the end of a two-year project where the UMZC has worked alongside the Wildlife Trust for Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire and Northamptonshire (WTBCN) to link historical Museum butterfly specimens with modern conservation initiatives, engaging new audiences with wildlife both past and present.

The UMZC and WTBCN partnered on an extensive public engagement programme, carrying out events at local schools in Cambridgeshire, at the UMZC and on WTBCN reserves. A huge amount of online content was also produced to reach people during lockdown. From wild crafts and minibeast hunts, to live Q&As and Museum tours, over 50 events were carried out, reaching more than 2,000 participants, while the online content attracted an even larger audience, with more than 5,000 views and downloads. The exhibition is the latest public engagement event in this programme, and it will be running until the 18th September 2022.

Butterflies Through Time

The Butterflies Through Time project was funded by the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, which specifically supports initiatives that increase access to underutilised museum collections to achieve social impact. Therefore, selecting which Museum specimens would underpin the project was an important choice.

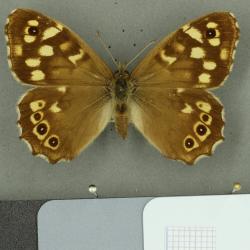

The insect collection is the largest single collection in the UMZC, containing around a million specimens, and represents the last major section yet to be fully catalogued. Some of the insects are amongst the oldest and most fragile specimens in the Museum, being collected over the last 200 years by famous naturalists of the day. Many specimens are also from some of the country’s oldest nature reserves, some of which are still actively managed for conservation. Therefore, the Museum’s insect collection represents a unique long-term dataset which allows the scale of biodiversity change in the UK to be tracked into the past. However, with the time and funding available, it would not have been possible to carry out a project on all one million specimens in the insect collection. This meant we had to choose a specific group of insects to focus on, and we chose the butterflies of the UK.

Butterflies are a charismatic group of insects that most people think of in a positive light. In this way, they are a ‘gateway insect’ that can be used to engage audiences with the importance of invertebrates more generally and the challenges they are facing. For example, although cockroaches are extremely important for recycling nutrients and breaking down decaying matter, it would likely have been more difficult to make audiences care about their population declines.

Butterflies also have complex lifecycles that make them sensitive to environmental change. This means that declines in their populations can indicate wider problems, impacting a range of different species living in the same habitats. Therefore, long-term trends in museum butterfly collections can be linked to stories of habitat change, climate change and sustainability.

For these reasons, the UK butterflies were the perfect group to focus on. The idea for the Butterflies Through Time project was for the UMZC to provide a record of change over the last two centuries using these historical butterfly specimens, which could then be complimented by modern conservation practitioners engaging audiences with local wildlife. This work has culminated in putting more physical specimens on display during the current exhibition at the UMZC, so that the stories they tell can be shared with the public.

The Exhibition

Historical museum specimens allow us to see what animals were living in different environments hundreds of years ago and compare them with those that are still around today. In this way, they can act like time-machines and show us how much things have changed. This helps us understand what has been lost but can also build an appreciation for the wildlife that remains.

The Butterflies Through Time exhibition uses UK butterfly specimens from the UMZC collections to showcase 13 local species and the changes they have experienced in Cambridgeshire over the last 200 years. This offers visitors a chance to see rare butterflies that are usually held behind the scenes in the Museum storerooms. On pillars across the Museum galleries, striking 2m-tall displays show the modern researchers and conservationists working with these species to reverse long-term declines.

Elsewhere in the Museum galleries, we feature 19th-century naturalist Leonard Jenyns, whose historical records inform much of the exhibition. Jenyns spent a lot of his time recording local wildlife in Cambridgeshire, and his detailed notebooks are now held at the Museum.

However, as important as it is to share historical records of loss, it was important that the exhibition did not simply convey a message of doom and gloom. Therefore, Jenyns’ notes on past declines feed into displays on modern conservation work, which is restoring and enhancing butterfly habitats for the future. A huge amount of this work is being carried out by WTBCN, including wetland restoration at the Great Fen and future-proofing against climate change with the Banking on Butterflies project.

Last but certainly not least, the exhibition features artwork made in collaboration with students from local schools, who have worked with artists and researchers to engage with butterflies, other insects and their local green spaces.

The 13 species featured in the exhibition are only a fraction of the butterflies found in the UK. For more details, including a full list of resident species and how you can help conserve butterflies in your garden or local green space, please visit the exhibition’s page on the Museum of Zoology’s website.

Leonard Jenyns and historical records

Leonard Jenyns was a naturalist who lived in Cambridgeshire during the 1800s. He was a contemporary of Charles Darwin and was one of two men offered a job onboard the HMS Beagle, to travel the world on a voyage of discovery, before turning it down and suggesting Darwin as a replacement. After declining this offer, Jenyns never once went abroad but lived in Cambridgeshire for nearly 30 years, working as a reverend. In his free time, he liked nothing more than to record the wildlife around him, and in four beautifully handwritten notebooks, Jenyns took it upon himself to record every single species he and his friends found in the county. This is a really rare resource as it provides us with a near comprehensive list of the wildlife that lived in Cambridgeshire 200 years ago, with details such as key sites for species and how common they were. This allows us to peek back in time and compare Jenyns’ records with what can be seen today and see how much has changed.

For example, one of the species featured in the exhibition is the swallowtail butterfly. Leonard Jenyns’ notebooks highlight that this species was once common in Cambridgeshire: ‘Found in the greatest plenty, throughout the Fens between Ely & Cambridge.’

However, the swallowtail became locally extinct in Cambridgeshire the 1950s after a long period of progressive drainage when its fenland habitats were converted to farmland. The butterfly’s disappearance mirrors declines in many wetland species that were previously found in the county.

Nationally, the swallowtail butterfly now only survives in the Norfolk broads. Reintroductions have been attempted at Wicken Fen in Cambridgeshire but have ultimately failed. Its food plant, milk parsley, needs to grow large enough and in high enough numbers in order to support stable populations of the butterfly. It is thought that, in the past, Wicken Fen may have been too dry for food plants to reach full size, or there may simply not have been enough habitat available.

Hopefully, wetland restoration projects like the one being carried out at the WTBCN’s Great Fen, which is working to re-wet a vast 3,700-hectare landscape, could provide enough habitat to support this species in Cambridgeshire once again.

Modern conservation and PhD work

It is important to make people aware of past declines, but we also want to promote a positive message to go along with this rather than making people feel powerless. Initiatives like that in the Great Fen are great positive examples of conservation work bringing once biodiverse habitats back to life.

Moving away from the past and looking to the future, climate change is projected to become a leading cause of biodiversity loss. This is where my PhD research comes in. Once again, working alongside WTBCN I will be carrying out research on the Banking on Butterflies project. This initiative has taken flat, ex-arable land on nature reserves and built artificial banks to create a varied landscape with a wide range of microclimates. We hope that, as regional temperatures continue to rise, these features will provide more options for species on isolated nature reserves and temperatures that remain suitable for them into the future.

For more information on how we can all engage with and protect wildlife where we live, please visit the ‘Things You Can Do’ page on the Museum of Zoology’s website.

March 2022 -

Protecting one of our smallest critters: Our research on the small blue butterfly

This blog post was written by Esme Ashe-Jepson, a PhD student in the Insect Ecology Group. Please hover over the images for captions.

During the first lockdown, when I was not allowed to go into the field to collect the data I had planned on, I was instead offered some old data from over 10 years ago that had been forgotten about to keep me busy. It was data on where the small blue butterfly lays its eggs. When I was finally given permission to go out to the field, but only for a few weeks, I focused my energy on recollecting similar data, which meant I could compare how this butterfly laid its eggs over a 14-year timeframe, and whether their preferences have changed over time.

This was my first taste of fieldwork during my PhD, and I was lucky enough to enjoy bright sunny days in wildflower meadows, searching the strange, fluffy kidney vetch flowerheads for the elusive small blue caterpillars and eggs.

The small blue is a challenging butterfly to work with, and I’m sure a bit of a nightmare for conservation practitioners. Firstly, they don’t fly very far, which means they form small, isolated populations which can disappear after a single bad season. Secondly, female small blues will only lay their eggs on a single species of plant, called kidney vetch. This plant is not overly common and requires disturbed soil to germinate and grow in good numbers. This can be difficult to achieve on protected land. Thirdly and perhaps strangest of all, the caterpillars have a distasteful habit of cannibalising each other. This means that it doesn’t matter how many butterflies you save, and it doesn’t matter how many foodplants you carefully nurture; if all the butterflies lay their eggs on the same plant, there will be a Battle Royale ending in only a single survivor. We found evidence for this happening back in 2006, where the numbers of kidney vetch dropped and suddenly there were as many as 16 eggs being recorded on a single flowerhead, followed by a population crash the following year. Our goal is to encourage the small blue to lay as many eggs as it can, but only one egg per flower.

What we found was that female small blues prefer certain characteristics on a kidney vetch flower in order to lay an egg on it, and that these preferences had not changed over 14 years, implying that management for the small blue can also be consistent. These characteristics are that the flower is tall, sticking out from the surrounding vegetation, and that it should be surrounded by tall vegetation. This can be achieved quite easily, where conservation practitioners protect patches of kidney vetch from grazing animals or being trampled or cut. This can be a bit of a challenge in the case of rabbits, as I encountered in the field. The nature reserve I was working in had rabbits, which have a strange habit of chewing through the stems of kidney vetch flowers, leaving the flower to rot on the ground while the caterpillar wastes away. I remember many a disappointing day, returning with high hopes to the plants I had found small caterpillars on, expecting to have seen them grow fat, but ended up finding a pile of rotting flowerheads on the ground. Sheep will also eat kidney vetch and are commonly used for grazing in nature reserves. Without knowing that small blues need these tall flowers, and that these flowers are particularly tasty to herbivores, management for this species would be challenging and frustrating.

With this information, conservation practitioners managing nature reserves with small blues can make some small changes to help maintain these strange little butterflies that are an integral part of our landscape.

You can read the published paper for free by clicking here.

February 2022 -

A Q&A with new research assistant, Evie Crouch

This blog post was organised by Kate Howlett, a PhD student in the Insect Ecology Group.

What is your new role in the Group?

EC: I’m a research assistant for the Butterflies Through Time project with the Insect Ecology Group where I have been helping coordinate outreach events with the Public Engagement Team at the Museum of Zoology. At the moment, I’m assisting the curation of the Butterflies Through Time exhibition, which will run from the 15th March to the 18th September 2022. As part of my job, I’ll be delivering engagement events here at the Museum and at different nature reserves around Cambridge later on in the year, and I will be helping to create a digital catalogue of the specimens we have here in the museum.

If you’re interested in the Butterflies Through Time exhibition, please come along to the Departmental preview at 4pm on the 9th March where you can find out more from myself and others involved with the exhibition.

What led you here?

EC: I first started studying butterflies in my second year at university on a course trip to Eswatini. I was told by lecturers that they were a good taxon to survey due to their sheer numbers and beauty – and they weren’t wrong. From there I went on to do my undergraduate dissertation on how different environmental parameters affect butterfly diversity in woodland habitat at a site back home. I then followed this up by looking at how different farmland management types affect pollinator abundance at Wild Ken Hill in North Norfolk, for my master’s dissertation last summer.

What first sparked your interest in Museums and science communication?

EC: I always loved going to the Natural History Museum when I was younger, but the science communication module I did in my third year was what really sparked my interest in public engagement and outreach. I love the idea of being a ‘middle-man’, someone who understands the science and can translate it in a way that is engaging to others – that way you can bring a bit of creativity into it as well.

What is your favourite part of the job?

EC: I love the fact that the job is so varied, and I get to try out different tasks – for instance I’ve never put on an exhibition before! I also like that I get to communicate with lots of different people and engage people with the things I find interesting.

What’s been the most interesting or valuable thing you’ve learned so far?

EC: Probably the experience of helping to curate an exhibition and the insight into all the things that involves.

What are you looking forward to?

EC: I’m really looking forward to delivering all the engagement events we have planned this month to go along with the exhibition launch, although I’m especially looking forward to any I can do outside later in the year, as children become more engaged when they’re outside and can learn in a much more hands-on way.

What are you hoping to do next?

EC: I’d love to stay in public engagement when my contract ends in summer. What exactly, I don’t know yet!

January 2022 -

A Q&A with new research assistant, Josh Jones

This blog post was organised by Kate Howlett, a PhD student in the Insect Ecology Group.

What is your new role in the Group?

JJ: For the next six months, I’ll be working as a research assistant on our smallholder oil palm project in Indonesia and Malaysia. The project will be looking at how management decisions affect yield, biodiversity, and ecosystem processes like pollination. This is really exciting because, although there’s been a lot of research on improving the sustainability of industrial oil palm, there hasn’t been much work on smallholders. On a day-to-day basis, my job will involve coordinating with our collaborators out in the field, managing data after it’s been collected, and eventually helping to analyse and write up the results.

What led you here?

JJ: Before this I was a master’s student on the Tropical Forest Ecology course at Imperial College London. After I finished, I was looking for a research position to get more experience, and this job was a perfect match for my research interests, which focus on promoting biodiversity and sustainable development in the tropics. It also meant I could get paid to do what I was most passionate about, which is crazy.

What first sparked your interest in tropical ecology?

JJ: It sounds really boring, but it was writing an essay before my undergraduate field course to Borneo. The essay was on the Janzen-Connell hypothesis, which describes how insects and fungi shape tree diversity in tropical forests. It was an interesting, if not slightly controversial, concept, and I really enjoyed getting to think about the complexity of tropical systems. Once I got to Borneo, I ended up enjoying the fieldwork as well (which is possibly less surprising) and decided that was a good sign that this was the area of research I wanted to go into.

What is your favourite part of the job?

JJ: The variety. I’m not going to be clichéd and say that every day is different, but I do get to try a lot of things. I could be writing up protocols, having video calls with researchers in Southeast Asia, creating field site maps, applying for permits, setting up collaborations, or finding new ways to improve the reproducibility of our data. This term, I’m even going to start teaching undergraduate students, which I wouldn’t have imagined I’d be doing at the University of Cambridge, certainly not in my 20s anyway.

What’s been the most interesting or valuable thing you’ve learned so far?

JJ: One of the differences I’ve noticed from doing research as a master’s student is everything is much more collaborative. I’m not just focusing on one small project — I’m working with PhD students in our group, with our PI, and with collaborators in the UK, Indonesia, and Malaysia. I think it makes it a bit more interesting as it often leads to some unexpected opportunities, but you do have to be a lot more organised as at any one point there’ll be several loose threads to keep track of.

What are you looking forward to?

JJ: Like all researchers, I’m looking forward to seeing the results! We also have a citizen science project being led by our PhD student Martina Harianja, in which farmers send in butterfly photos taken on their plantations. It will be nice to see more of those, especially as we won’t be going out to the field anytime soon.

What are you hoping to do next?

JJ: Right now, I’m applying for PhDs, so hopefully that will be the next big step. Over the last few years, I’ve developed an interest in how tropical plant communities are structured and how we can use that knowledge to restore them, so I’m hoping to focus more on that side of things. Moving to the plant side is possibly a bit of an unexpected move for someone working in the Insect Ecology Group at the Department of Zoology, but I’m excited to see how things will go.

December 2021 -

New paper: 'Effects of COVID-19 lockdown restrictions on parents’ attitudes towards green space and time spent outside by children', published in People and Nature

This blog post was written by Kate Howlett, a PhD student in the Insect Ecology Group and lead author of the paper. Please hover the images for captions.

Children in the UK today have less daily contact with the natural world than previous generations. Yet we know that experiences in nature at a young age are important for wellbeing, skill development and health, as well as for inspiring future support for conservation. This increasing disconnect from nature is often blamed on a growing proportion of the population living in urban areas. During the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdown restrictions limited people’s contact with nature to the green spaces immediately accessible in their local neighbourhoods. In the UK, fewer urban households have gardens than those in rural areas, where the gardens also tend to be larger. Therefore, lockdown restrictions in the UK may have exacerbated differences in access to nature and experience between urban and rural children.

In our new paper, published in People and Nature, we explored whether lockdown restrictions in the UK exacerbated or reduced differences in green space experience between urban and rural groups. Via an online survey, we explored attitudes towards green space amongst a sample of 171 parents from Cambridgeshire and North London, in the southeast of the UK. We asked whether lockdown had affected parental views on the importance of green space or the amount of time their children spent outside, and we assessed whether there were differences in responses between urban or rural areas.

The majority of parents in urban areas reported wanting their children to have more access to green space than they currently had, whilst the majority of parents in rural areas said they were happy with the amount of green space their children had access to. We found that most rural parents reported being aware of the importance of green space before lockdown, whilst most urban parents said that lockdown had made them realise the importance of these spaces, when they had taken them for granted before. Finally, urban children generally spent less time outside during lockdown, whilst rural children spent more time outside.

Collectively, our results suggest that lockdown may have exacerbated pre-existing green space inequalities between urban and rural children in our sample, with implications for children’s wellbeing and connection with nature. We suggest that interventions targeted towards urban children are important in ensuring equality of nature experience amongst children from different backgrounds.

You can read the newly published paper for free by clicking here.

October 2021 -

An unexpected journey

This blog post was written by Esme Ashe-Jepson, a PhD student in the Insect Ecology Group. Please hover over the images for captions.

¡Buenos días!

At the end of September, I travelled to Panama for six months to join a research team at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) working on tropical butterflies. This wasn’t a part of my original plan for my PhD but rather the result of a conversation started between the research groups. STRI wanted someone to collect tropical butterfly thermal buffering data, and a member of our group had recently published a great method for doing exactly this on temperate species. By collecting similar data, we will not only have a valuable dataset on a vastly understudied group of insects, but this will also facilitate a comparison between temperate and tropical species, highlighting any differences in how the groups may respond to climate change.

I landed in Panama City, where I was going to be staying for four days to settle and collect my credentials before heading to Gamboa, a small town on the edge of the jungle. Compared with late September in Britain, the weather was scorching hot and very humid. The drive from the airport was lined with palm trees, the sky filled with black vultures and frigate birds. There were miniscule geckos in the flat I was staying in, lapping up the tiniest ants I’ve ever seen. From the balcony, I could look across the old town with their mismatched roofs and narrow streets to the skyscraper central of Central America. The people were friendly and helpful, even with my very poor Spanish (but I’m learning).

I then headed to Gamboa, where I would be staying for the next six months. I was warmly welcomed and met what felt like the whole town in one afternoon. I was joined by an amazing team of young ecologists, all bringing their own skill sets to the project. We work primarily on Pipeline Road, a road built into the jungle many years ago by the Americans alongside a fuel pipeline, but the road was never finished. Now, it is a local hotspot for seeing birds and conducting research. We walk a few kilometres into the jungle three or four days a week to catch butterflies and collect our data. Alongside the many beautiful butterflies, we also saw many other animals I’ve never personally seen in real life, like toucans, monkeys and the ever-present ñeque, as it’s locally called, a strange large rodent with long deer-like legs. I have yet to see a sloth, but I’ll keep looking into the trees until I do.

Data collection is hard. I’m out in the field many hours less than I usually am in the UK, but am exhausted from the heat, humidity and biting insects by noon, which turned out to be lucky since in the wet season (as it is now), the storms usually hit in the early afternoon.

There is so much in the tropics, and there is so much we still don’t know. Research here has barely begun, and there is so much value in working here, but I am always conscious of my position as an outsider and the risk of doing ‘helicopter research’. This is where researchers from wealthier countries go to a developing country, collect data, travel back to their country, and analyse and publish the data with little or no involvement of the local researchers. This does not provide the local contributors with the recognition they deserve, and can impact their careers and future development.

I am blessed to be working with a range of researchers from around the world and locals from Panama; it is extremely important to me that we all learn from each other and all benefit from this research. As a team, I am learning fieldwork skills from a seasoned veteran of the forest, and butterfly identification and knowledge from a local young expert, and I am teaching them how to build and conduct a research project with a specific goal. The primary goal of all my research is to improve conservation, and this cannot be done effectively without the local people’s involvement. I look forward to hopefully staying in touch with many of the amazing people I have met here, especially the young ecologists where you can feel their passion for the subject and know they will excel in their field if given the chance.

I never expected to end up here; it’s still a strange and surprising place to wake up every morning. I am incredibly lucky, and I look forward to not only finding out what our data can tell us about tropical butterflies and sharing this with our local contributors, but also to continuing my adventure here and hopefully learning some more Spanish along the way.

¡Hasta luego!

September 2021 -

Interning (remotely) at the Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology (POST)

This blog post was written by Kate Howlett, a PhD student in the Insect Ecology Group. Please hover over the images for captions.

In the third year of my PhD in zoology, I took some time out to work as a Postgraduate Fellow at the Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology (POST). This placement is offered as part of the UKRI Policy Internship Scheme, available to PhD students funded by UKRI Research Councils, and POST is just one of 22 host organisations offering placements.

There is a large range of placements available, with each host organisation offering something slightly different, so, if you’re interested in learning about policy, there will definitely be something for you. I applied to POST because they offer the chance to work independently on a policy briefing on a pre-assigned topic. I thought the opportunity to produce a briefing would be a great way of learning about how research feeds into policy first-hand – and I was right!

Part of the appeal of applying to and working at POST is also the chance to work on the Westminster Estate, meeting parliamentarians and exploring the House of Commons and House of Lords. For obvious reasons, this couldn’t happen in the end, and the entirety of my placement was done remotely via a parliamentary laptop, which I was loaned, but it was still really interesting to see how Westminster works remotely.

During my placement, I produced a policy briefing on environmental housing standards in the form of a POSTnote, which is POST’s flagship briefing format. These are four-page, concise briefings that lay out impartial information on a topic relating to science or technology. The purpose of these is to provide parliamentarians with up-to-date, unbiased information so that they can make informed decisions.

The process for producing a POSTnote is well laid out and quite straightforward – very different to a PhD project – so working on such a streamlined task can be a welcome break to research! The process involves first conducting your own research to bring yourself up to speed with the topic and the relevant policy landscape, and using this to create a list of potential interviewees who can contribute expertise. Interviewees are spread way beyond academia, encompassing industry, government (both local and national), regulatory bodies, NGOs, charities and any other relevant independent institutions. Next, you need to interview as many people as you can – I interviewed 27 people – to find out all about your topic and where the relevant literature is.

Then, you can start drafting your briefing to encompass everything you’ve learned. This can be challenging because you need to make sure that opinions and information are unbiased with respect to your stakeholders and that all the information is accurate and up-to-date. It’s also important to avoid making recommendations since this isn’t something that is in POST’s remit. I found this bit really difficult since it felt like I was just producing a list of problems without providing any solutions. But this varies quite a lot depending on your topic; mine was very much an overview of all the relevant areas, rather than an in-depth look at a particular technology or issue.

After several drafts, and both an internal and an external review process, the briefing gets published on the POST website and circulated to parliamentarians in both the House of Commons and the House of Lords. Sometimes, if your topic is particularly timely with respect to current legislation changes, a launch event can be arranged at which relevant stakeholders are asked to speak, all to help publicise the POSTnote.

I really enjoyed the whole process since it was a great opportunity to develop all sorts of professional skills, from interviewing and note-taking to a better understanding of Freedom of Information Requests and an in-depth knowledge on UK housing. It was fascinating to see how research interacts with policy to inform and guide decision makers. POST is also a really friendly place to work, and everyone is very approachable and happy to help. It’s also amazing to see how quickly people respond to you when you have a parliamentary email address! I would definitely recommend the experience to anyone thinking of a career in policy or anyone who is interested in understanding the science-policy interface, and I’m happy to chat to anyone who is thinking of applying.

August 2021 -

Mapping nature reserves: Three months with the Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire & Northamptonshire Wildlife Trust

This blog post was written by Jake Stone, a PhD student in the Insect Ecology Group. Please hover over the images for captions.

A key component of my BBSRC-funded Doctoral Training Partnerships PhD programme is carrying out a PIPS – a Professional Internship for PhD Students. This is a three-month placement hosted by an external non-academic organisation, the aim of which is both to give context to my PhD research project and to provide skills and opportunities that can be applied throughout and post-PhD.

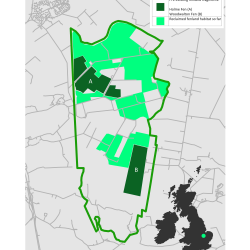

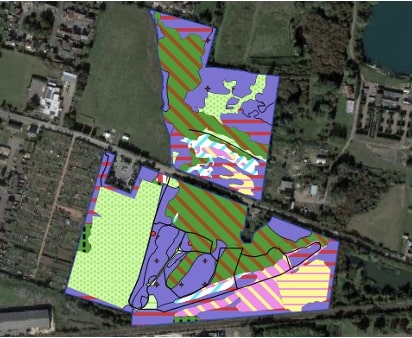

I have recently completed my internship with the Wildlife Trust for Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire & Northamptonshire (BCN). During my three months with the Trust, I worked on a project aiming to generate a habitat-based data set that can be used to calculate how much carbon is being stored, or sequestered, throughout all of the Wildlife Trust BCN reserve sites. This will serve as essential baseline information for future work carried out by the Trust on natural capital and carbon offsetting, as well as providing a visual framework to help log and guide management action across the BCN estate.

To achieve this, I first had to source and collate all pre-existing habitat-based information from National Vegetation Classification (NVC), Phase 1 and management maps held by the Trust. These were then georeferenced and, for each of the 50 reserve sites located in Cambridgeshire, new, up-to-date habitat polygon maps were created (see first image). These varied from a small pond with only a handful of habitat types, to a site like the Great Fen, which spreads over 3,700 hectares and represents a large variety of both land uses and vegetation cover. These new maps were then ground-truthed using a combination of recent aerial drone imagery and on-the-ground vegetation surveys. Overall, I created well over 2,000 separate habitat polygons, each with additional habitat and geographical data attached as well as relevant, up-to-date codes using the UK Habitat Classification System. Lastly, these data were combined with habitat carbon stock values and, using the wilder carbon tool, carbon sequestration figures were generated.

Although the majority of my time on placement was spent working from home at my laptop, I did get the opportunity to visit a few of the reserves to carry out vegetation surveys (see second image). This was a real highlight, with it being particularly rewarding to see sites that I had pored over digitally for hours in real life. It also allowed me to brush up on my plant identification skills and to appreciate just how botanically diverse and rich each of the reserves are.

I thoroughly enjoyed my time with the Wildlife Trust BCN; not only did I learn a whole bunch of new skills (including QGIS mapping software and habitat classification systems, which will be really useful to take forward into other projects), but it also allowed me to feel more connected with local wildlife, something that I was especially appreciative of during the last few months of Covid-19 restrictions.

July 2021 -

Looking for larvae at Totternhoe Nature Reserve

This blog post was written by Kate Howlett, a PhD student in the Insect Ecology Group. Please hover over the images for captions.

Towards the end of June, several members of the Group met up at Totternhoe Nature Reserve to combine a long-overdue Group get-together with some exciting data collection. PhD student Esme Ashe-Jepson is researching the foodplant preferences of a rare butterfly, the Duke of Burgundy. The Duke has suffered one of the worst long-term declines of any UK butterfly, so understanding how adults choose which plants to lay their caterpillars on is vital if we are to reverse these downward trends.

Totternhoe Nature Reserve is managed by the Wildlife Trust for Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire and Northamptonshire, and conservation practices here are being informed by the latest research into butterfly habitat preferences. It’s hoped that by following the latest guidelines, the Reserve can offer habitat that is resilient to climate change, so that UK butterflies such as the Duke can continue to grow their populations as the climate continues to change.

The Duke lays its eggs on cowslip, and, once the larvae hatch out, they feed on the leaves, leaving behind characteristic feeding damage. The caterpillars start to hatch out in June and feed throughout the night. So, several of us packed our torches and headed out to Totternhoe in the early evening to see how many larvae we could find. This involved quite a lot of crawling through hawthorn bushes and up and down slopes, trying our best not to cause too much damage, but a sunset dinner break made it all worth it.

For each larva we spotted, Esme recorded the temperature of the air, the temperature of the leaf on which it was feeding, and the temperature and body length of the larva. This will help her answer questions about the Duke’s foodplant preferences and the microclimate around them, and how these might be helping to buffer fluctuations in wider air temperature. This research will help inform management decisions, such as where cowslips should be encouraged to flourish, to maximise the population of Dukes that the Reserve can support.

As well as finding lots of Duke larvae, we also spotted some other great wildlife throughout the evening. This included plenty of Marbled Whites, a Dark Green Fritillary, several Chalk Hill Blue larvae and Burnet Moth larvae, some screaming swifts, and the eerie and persistent calling of a Muntjac, no doubt wondering why there were humans clambering around the slopes at midnight.

June 2021 -

New paper: Conserving an endangered butterfly into the future – long term requirements of the Duke of Burgundy

This blog post was written by Matt Hayes, a research assistant in the Insect Ecology Group and lead author of the paper. Please hover the images for captions.

Seeing butterflies on the wing is usually a sure-fire sign that warmer weather has arrived and, for most of us, I hope they are a common sight on sunny days in spring and summer. In fact, one of my favourite things about butterflies is that they tend to completely avoid bad weather and are most commonly seen between the hours of about ten in the morning and four in the afternoon, making them the perfect study group for fieldwork!

Butterflies are relatively large insects, which are often very colourful and fly up in the air, so they can be easy to observe. As such, these beautiful animals have captured the imagination of humans for centuries and have a long history of recording, especially in the UK.

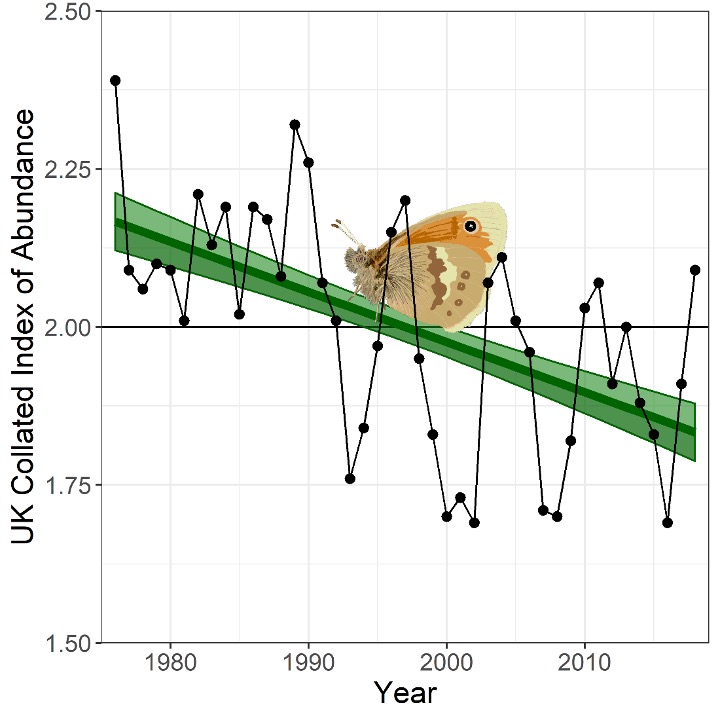

However, numbers are declining, with the most recent State of the UK’s Butterflies report in 2015 highlighting that more than three quarters of our resident and regular migrant species have suffered declines in abundance or distribution since the 1970s.

What’s even more worrying is that butterflies are useful indicator species, and monitoring their numbers can warn us of wider reaching negative changes taking place around them. Butterflies have a complex life cycle with different life stages: starting out as an egg before turning into a caterpillar, and later forming a chrysalis and undergoing metamorphosis into an adult butterfly. These distinct life stages often need different specific requirements to survive, and, as such, butterflies can be very sensitive to even small changes in the environment. Therefore, if we look after our butterflies, we can catch potential problems early and look after a whole range of other species in the process.

In order to conserve butterflies and their associated communities, we need studies to investigate the consistency of their habitat and climatic preferences over multiple years. Only then can management plans be put in place to protect them successfully in the long term. This will be particularly important as climates continue to warm, with concerns that species sensitive to environmental change will find those nature reserves currently supporting becoming unsuitable in the future. That is why our latest paper examined the requirements of an endangered butterfly, using data collected over a 14-year timeframe.

The Duke of Burgundy butterfly has suffered one of the worst long-term declines of any butterfly species in the UK. Conservation efforts and global warming may have helped stall this downward trend in recent years, but more research is needed if declines are to continue reversing. In this paper, we looked at the preferences exhibited by Duke of Burgundy butterflies when selecting foodplants for their caterpillars and investigated whether these preferences could be replicated through current management techniques. Data were collected from Totternhoe Quarry Reserve, a chalk grassland site owned and managed by the Wildlife Trust for Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire and Northamptonshire.

The Duke of Burgundy was found to be extremely consistent in its preferences over the course of the study, with large, sheltered groups of its foodplant, cowslip, being chosen year on year. The current management technique of clearing scrub is doing a great job of maintaining high numbers of cowslips on site, but care needs to be taken to leave long enough between clearance for the plants to grow large enough amongst shelter to encourage the Dukes to lay eggs. These results highlight that specific management plans need to continue in order to support this selective butterfly.

Whether preferences remain the same, as with the Duke of Burgundy, or vary from year to year, maintaining suitable conditions will only get more difficult as climates continue to change. The continued conservation of endangered species will be made more feasible by increasing heterogeneity on reserves, and management plans that promote habitat and topographic variability are set to become increasingly important.

May 2021 -

New paper: ‘Systematic mapping shows the need for increased socio-ecological research on oil palm’, published in Environmental Research Letters

This blog post was written by Valentine Reiss-Woolever, a PhD student in the Insect Ecology Group and lead author of the paper. Please hover over the images for captions.

Several of our group members conduct research on oil palm, a prolific and often controversial crop responsible for 40% of the world’s vegetable oil used in food, cosmetics and biofuels [1]. From large-scale ecosystem services, to social equity, to the diversity of spiders and ants living within plantations, there is a wide range of ways to study the tropics’ most rapidly expanding crop. Our group resides within the Department of Zoology, and we maintain a largely zoological research focus. However, it is impossible to ignore the importance of innovative and interdisciplinary research to inform sustainable management of agricultural landscapes. While the oil palm industry contributes to the rapid loss of native forests, it also provides employment for over 4.5 million farmers in Southeast Asia alone, illustrating how the crop’s cultivation affects both human and non-human communities [2].

As research investigating the effects of different cultivation techniques increases, it is crucial for review papers to amalgamate findings and identify knowledge gaps. Several such reviews on biodiversity in oil palm have been produced by our group previously [3, 4], and these have been vital to the past decade’s understanding of oil palm and in advocacy for purposeful research direction.

Our new paper, published in the April edition of Environmental Research Letters [5], is the result of a collaboration between several group members and uses a systematic mapping approach to review existing social, ecological and socio-ecological research on oil palm cultivation. Systematic mapping is a procedure that identifies, classifies and describes a body of evidence [6] in a systematic, rigorous way. Simply put, a systematic map quantifies what research has been conducted and how, rather than offering a critical appraisal of the findings.

In our case, we asked the question: ‘What has been the social, ecological and socio-ecological focus of research on oil palm, and how has it been conducted?’. This involved a strict approach to literature searching, evaluation and classification. Fortunately, one of the paper’s co-authors was Gorm Shackelford, who has worked with the Cambridge Conservation Evidence group on some of the most well-regarded systematic mapping guidelines [7].

Our search for the ecological, social and socio-ecological effects of oil palm generated 4,959 results from several databases. After a (very!) large amount of time had been dedicated to understanding the aims and content of each publication, 443 publications were deemed relevant to our key question. These were then classified by their research focus and methodologies, based on established systematic mapping protocols [8], allowing us to understand which concepts and study scopes received the most research attention. We examined the publications in the context of trends in oil palm production, sustainable certification priorities and recognised causes of yield gaps, and our findings identified key areas where research effort is lagging behind requirements for sustainable, high-yield oil palm production.

We found a global increase in oil palm research over the past three decades, with a clear bias towards research conducted in Malaysia and Indonesia. This mirrors the fact that 85% of global palm oil is produced by these two countries [9]. Over 70% of the publications focused on ecological outcomes, 19% on social outcomes and less than 10% on interdisciplinary outcomes. We found three of the ten highest palm oil producing countries (Ecuador, Côte d’Ivoire and Honduras) were absent from the literature.

Currently, 10% of the world’s agricultural land is devoted to oil palm, with a variety of plantation structures and management techniques, including differing chemical inputs and planting strategies. This variability has effects on yield, ecological sustainability and worker conditions, as has been observed through our group’s work on the BEFTA and SAFE projects. Our review found that further research is required to inform truly sustainable plantation management. The most pressing areas are the effects of mono- versus poly-culture systems and the effects of management interventions on ecosystem services other than yield.

The purpose of any review is to expose knowledge gaps so as to best direct future research efforts. Given the multiple knowledge gaps identified in this study, we suggest that research priority should be given to areas with tangible benefits for management or wellbeing. This includes research that can inform management choices to benefit both social and ecological outcomes, such as intercropping with consumable crops to help smallholders avoid nutritional deficits while also creating a more diverse habitat for pollinators.

Several of the research biases we found in the literature are even reflected in the focus of our lab, which works mostly in Indonesia and Malaysia on invertebrate biodiversity studies. However, our group seems to be progressing along positive research trends: for example, we are now incorporating social surveys into BBSRC-funded research, and group member Michael Pashkevich has recently received funding as a Marshall Sherfield Fellow to expand oil palm research to Liberia. We aim to contribute to pressing knowledge gaps through our extended work with smallholders on both social and ecological concepts, and with Meg Popkin’s upcoming work on pollinator diversity. Our new publication represents the most extensive evidence mapping exercise of the interdisciplinary oil palm plantation literature to date, and we’re already looking forward to a 2030 review showing just how far we’ve come.

You can read the newly published paper for free by clicking here.

References

[1] Prokurat, S. (2013). Palm oil—Strategic source of renewable energy in Indonesia and Malaysia. Journal of Modern Science, JoMS 3/18/2013, 425–443.

[2] Vermeulen, S. (2006). Towards better practice in smallholder palm oil production. International Institute for Environment and Development.

[3] Turner, E.C., Snaddon, J.L., Fayle, T.M., Foster, W.A. (2008). Oil palm research in context: identifying the need for biodiversity assessment. PLoS ONE 3(2). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0001572

[4] Foster, W. A., Snaddon, J. L., Turner, E. C., Fayle, T. M., Cockerill, T. D., Ellwood, M. D. F., Broad, G. R., Chung, A. Y. C., Eggleton, P., Khen, C. V., & Yusah, K. M. (2011). Establishing the evidence base for maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem function in the oil palm landscapes of South East Asia. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 366(1582), 3277–3291. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2011.0041

[5] Reiss-Woolever, V.J, Luke, S.H, Stone, J., Shackelford, G.E., Turner, E.C. (2021) Systematic mapping shows the need for increased socio-ecological research on oil palm. Environmental Research Letters, in press. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abfc77

[6] James, K. L., Randall, N. P., & Haddaway, N. R. (2016). A methodology for systematic 983 mapping in environmental sciences. Environmental Evidence, 5(1), 7. 984 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-016-0059-6